When you hear a drum pattern from West Africa, a sitar melody from India, or a blues riff from Mississippi, you’re not just listening to music-you’re hearing history, struggle, joy, and identity. Music genres aren’t just categories for playlists. They’re living records of how people live, suffer, celebrate, and resist. Every genre carries the fingerprints of the culture that birthed it. Understanding them isn’t about labeling songs-it’s about understanding people.

Blues: The Sound of Survival

Blues didn’t start as a genre you’d find on a streaming app. It started in the cotton fields of the American South, where enslaved Africans and their descendants turned pain into rhythm. The call-and-response structure? That came from work songs and church hymns. The bent notes and raw vocals? That was the sound of someone holding back tears but refusing to break. By the 1920s, blues had spread from rural plantations to city juke joints. Artists like Robert Johnson and Bessie Smith turned personal sorrow into universal language. Today, blues is the root of rock, soul, and even hip hop. You can’t understand modern American music without understanding blues-and you can’t understand blues without understanding the weight of Black history in the U.S.

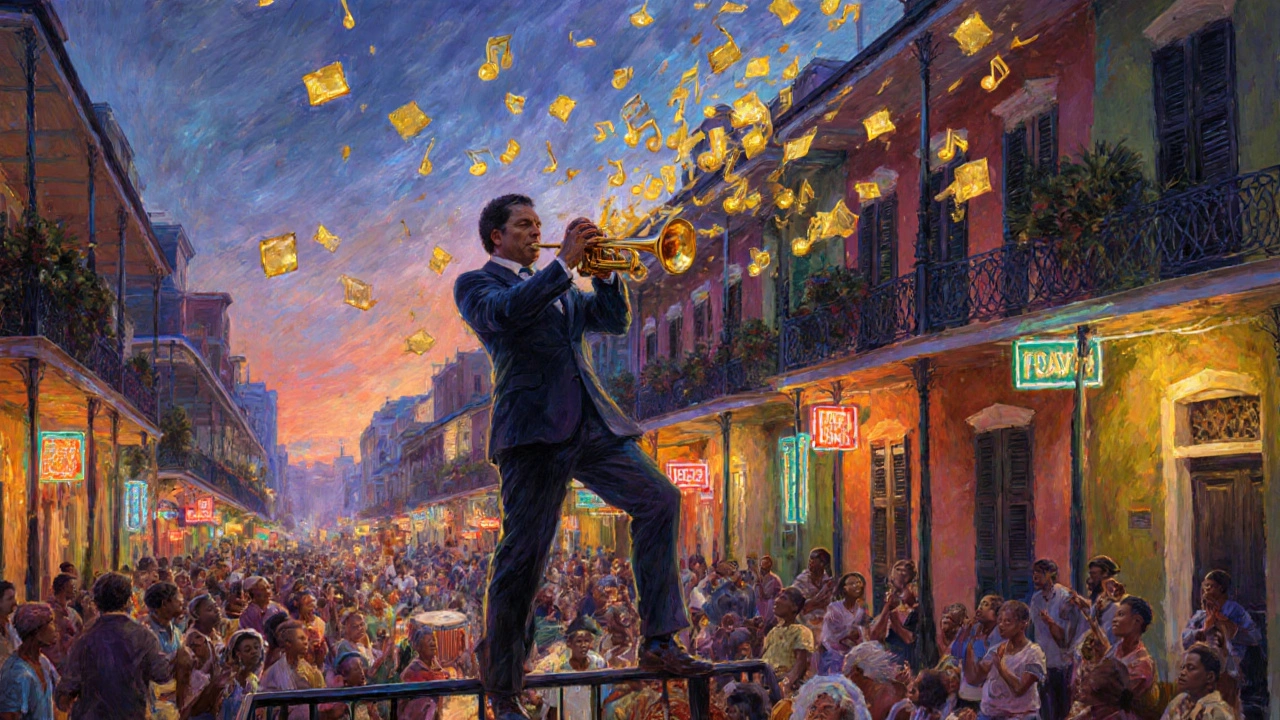

Jazz: Improvisation as Freedom

Jazz was born in New Orleans at the turn of the 20th century, where African rhythms met French harmonies, Spanish melodies, and Caribbean beats. It wasn’t written down-it was played by ear, shaped in the moment. That’s why jazz is called improvisation. It’s not just a technique; it’s a philosophy. In a segregated America, jazz became a space where Black musicians could assert their creativity on their own terms. Louis Armstrong’s trumpet solos weren’t just notes-they were declarations of individuality. Later, bebop artists like Charlie Parker pushed boundaries even further, using complex chords and fast tempos to reject commercial expectations. Jazz didn’t just change music. It changed how people thought about freedom, control, and expression.

Reggae: Rhythm as Resistance

Reggae didn’t just come from Jamaica-it came from oppression. After centuries of colonial rule and economic hardship, Jamaicans in the 1960s turned to music as a tool for spiritual and political awakening. The steady one-drop beat, the off-beat guitar chops, the deep basslines-they weren’t accidental. They mirrored the heartbeat of a people refusing to be silenced. Bob Marley’s songs like "Redemption Song" and "Get Up, Stand Up" weren’t just hits; they were anthems for global liberation movements. Rastafarian beliefs, with their focus on African roots and divine justice, became woven into the lyrics. Reggae didn’t just travel the world-it challenged it. From London to Tokyo, reggae gave voice to marginalized communities who saw their own struggles in its message.

Hip Hop: The Urban Storyteller

When you think of hip hop, you might picture flashy clothes or viral dances. But hip hop began in the Bronx in the 1970s as a response to poverty, disinvestment, and police neglect. Block parties became community hubs where DJs like Kool Herc spun breaks-short, rhythmic sections of funk and soul records-and MCs turned those beats into spoken poetry. Rap wasn’t just entertainment; it was testimony. Artists like Grandmaster Flash and Public Enemy told stories of life in abandoned buildings, of systemic racism, of dreams deferred. Hip hop’s four elements-DJing, MCing, breakdancing, and graffiti-were all acts of reclaiming space. Today, it’s the most popular genre in the world. But its core hasn’t changed: it’s still about telling truth when no one else will listen.

Flamenco: Grief, Pride, and Fire

Flamenco comes from the Andalusia region of Spain, shaped by centuries of Romani, Moorish, Jewish, and Spanish influences. It’s not just guitar and dance-it’s raw emotion made physical. The cante (singing) is often guttural, almost screaming. The footwork isn’t choreographed-it’s a rhythmic stamp of defiance. The palmas (hand claps) keep time like a heartbeat. Flamenco was long looked down on by Spain’s elite as "gypsy music," but it survived because it was too real to erase. In the 1950s, artists like Carmen Amaya and Paco de Lucía brought it to global stages, not as exotic spectacle, but as art rooted in deep cultural memory. Today, flamenco is recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage. It’s not performed for applause. It’s performed because it has to be.

Indian Classical: Time, Spirit, and Structure

Indian classical music doesn’t follow Western scales or fixed melodies. It’s built around ragas-melodic frameworks tied to specific times of day, seasons, and emotions. A raga played at dawn feels different than one played at midnight. The sitar, tabla, and tanpura don’t just make sound-they create atmosphere. Improvisation is central, but it’s not random. It follows strict rules passed down through generations. A single performance can last hours, not because it’s long, but because it’s meant to be meditative. This music isn’t about entertainment. It’s about connection-to the divine, to nature, to inner stillness. In a world obsessed with speed, Indian classical music reminds us that some things can’t be rushed.

Highlife: Joy in the Midst of Change

Highlife emerged in Ghana in the early 1900s, blending traditional Akan rhythms with Western instruments like guitars and horns brought by colonial soldiers and sailors. It was music for the urban middle class-people navigating new identities after colonial rule. The bright, danceable rhythms reflected optimism, even as the country faced political instability. Artists like E.T. Mensah turned highlife into a national sound. It wasn’t protest music like reggae or blues. It was music that said: we’re still here, we’re still dancing. Highlife influenced Afrobeat, and today, its spirit lives on in Ghanaian pop and Afrobeats. It’s proof that music doesn’t always need pain to be powerful. Sometimes, joy is the most radical act.

Why Genre Matters More Than Ever

In a world where algorithms suggest songs based on your mood, it’s easy to forget where music comes from. Streaming makes genres feel like interchangeable tags. But behind every genre is a people, a place, a history. When you listen to a mariachi band in Mexico, you’re hearing centuries of indigenous and Spanish fusion. When you hear a qawwali singer in Pakistan, you’re listening to Sufi devotion turned into sound. Genres aren’t just labels-they’re bridges. They let us walk into someone else’s world without leaving our chairs. Learning a genre means learning its context: the language, the politics, the spiritual beliefs, the daily rhythms of life that shaped it.

What Happens When Genres Lose Their Roots?

When a genre is stripped of its cultural context, it becomes a costume. Think of EDM festivals using African drum samples without crediting their origins. Or pop songs borrowing trap beats while ignoring the Black communities that built them. This isn’t appreciation-it’s extraction. Real understanding means knowing the history, honoring the creators, and recognizing when something is borrowed versus when it’s stolen. The best way to respect a genre is to go deeper: listen to the original recordings, learn about the artists, read about the social conditions that gave rise to the sound. That’s how you move beyond surface-level consumption.

How to Listen Like a Cultural Anthropologist

Want to truly understand music genres? Don’t just play them. Study them. Start with one genre that interests you. Find the earliest recordings-not the remixes. Read interviews with the pioneers. Watch documentaries. Learn the instruments. Understand the social climate when it was born. For example, if you love funk, find James Brown’s 1960s live shows and notice how the band locked into a groove like a machine. That wasn’t just style-it was a response to the Civil Rights Movement, a demand for precision and power. When you listen with context, music stops being background noise. It becomes a conversation across time and space.