Ever listened to a track and felt like it didn’t quite fit the label they gave it? Like when someone calls a song "hip hop" but it’s got the bassline of a 1990s jungle track and the vocal flow of a 2010s trap artist? That’s not a mistake. That’s the quiet chaos of subgenres - the hidden layers beneath the big labels we all know.

Why Subgenres Exist

Music genres are broad strokes. They’re useful for radio stations, playlists, and record store bins. But they don’t capture the nuance. Subgenres emerge when artists push boundaries, when technology changes how sounds are made, or when cultures blend in unexpected ways. A genre like rock might cover everything from Led Zeppelin to Green Day, but its subgenres - post-punk, grunge, math rock, glam metal - tell you exactly what to expect before the first note plays.

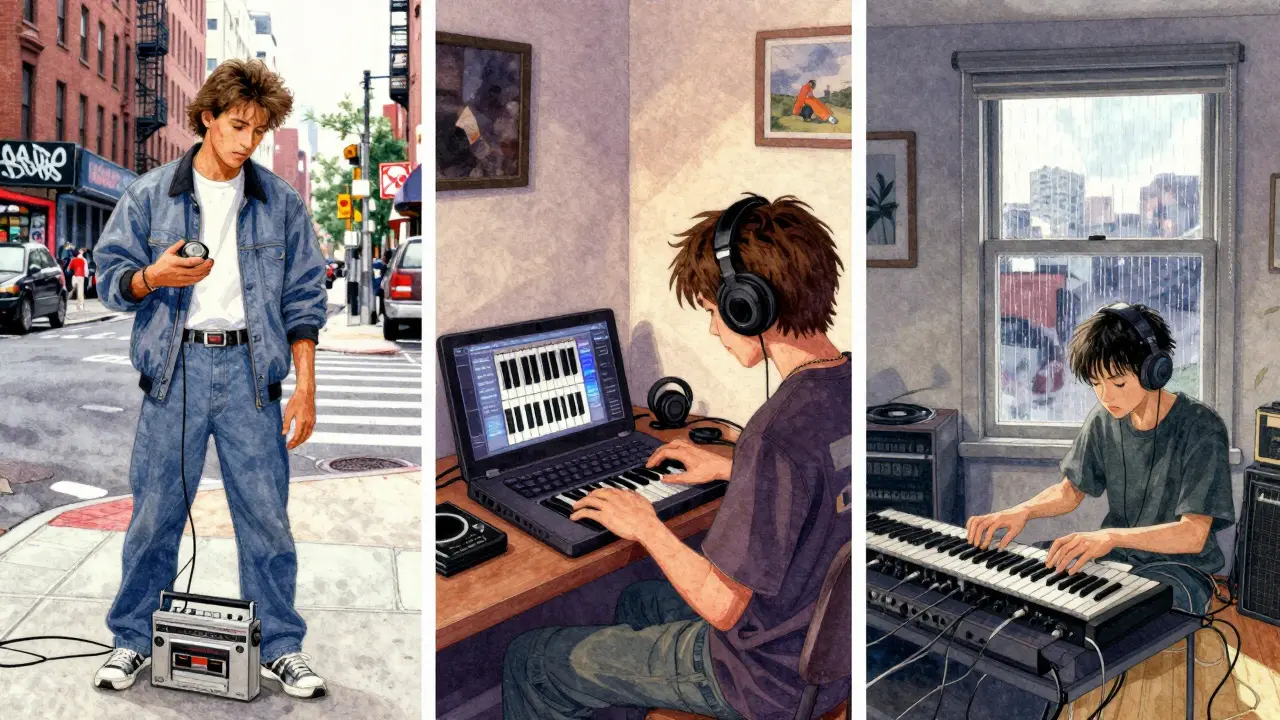

Subgenres aren’t just labels. They’re sonic DNA. They carry history, geography, and attitude. You can hear the industrial grit of Detroit in electro-industrial. You can feel the slow-burn soul of New Orleans in bounce music. They’re not made by academics. They’re made by kids in basements, producers on laptops, DJs in underground clubs.

Electronic Music: The Subgenre Factory

No genre has spawned more subgenres than electronic music. In the 1980s, house music came out of Chicago. By the early 90s, it had split into deep house, acid house, tech house, and progressive house. Then came trance, drum and bass, dubstep, future bass, and hyperpop - each with its own rhythmic fingerprint, tempo range, and emotional tone.

Take dubstep. Most people think of it as heavy bass drops and wobbly synths. But that’s only one branch - the UK bassline style that blew up in the 2010s. Original dubstep, from South London around 2001-2004, was darker, slower (138-142 BPM), and rooted in garage and reggae. Artists like Skream and Benga used reverb-drenched basslines that felt like they were echoing through a concrete tunnel. That version barely made it to mainstream charts. But it changed everything.

Today, subgenres like chillwave, vaporwave, and wonky aren’t just musical styles - they’re internet-born aesthetics. Vaporwave, for example, doesn’t just sample 80s elevator music. It critiques consumer culture through slowed-down yacht rock and pixelated mall imagery. You can’t understand it without knowing the meme culture that birthed it.

Hip Hop: The Ever-Evolving Grid

Hip hop has more subgenres than most genres combined. The difference between boom-bap and trap isn’t just tempo. It’s the attitude, the production tools, even the slang. Boom-bap, from early 90s New York, uses crisp snare hits, vinyl crackle, and jazz samples. Artists like Nas and Wu-Tang Clan built entire worlds inside those beats.

Trap, on the other hand, emerged from Atlanta in the 2000s. It’s built on 808s, hi-hat rolls that sound like rain on a tin roof, and lyrics about street life, drugs, and money. But trap itself split again: drill (Chicago, then UK), mumble rap, cloud rap, and even trap metal. Each one has a distinct vocal delivery, lyrical focus, and sonic palette.

And then there’s lo-fi hip hop - a subgenre that barely exists in clubs but dominates study playlists. It’s not about bars or beats in the traditional sense. It’s about atmosphere. Soft drums, dusty samples, vinyl hiss. It’s the sound of a rainy afternoon in a Tokyo apartment. No one set out to create it. It just happened because someone looped a jazz record and added rain sounds.

Rock’s Fractured Family Tree

Rock used to be one thing. Now it’s a thousand. Think about it: punk rock, indie rock, post-rock, shoegaze, stoner rock, emo, math rock, garage rock revival - each one has its own rules.

Shoegaze, for example, isn’t just loud guitars. It’s about drowning vocals in reverb, stacking layers until the melody becomes a wall of sound. Bands like My Bloody Valentine didn’t just make music - they built sonic environments. Their 1991 album Loveless used over 100 guitar tracks on some songs. That’s not rock. That’s architecture.

Math rock is even weirder. It’s defined by odd time signatures - 7/8, 11/16 - and complex, interlocking rhythms. Bands like Don Caballero or Slint don’t write songs. They write puzzles. You don’t dance to math rock. You try to count along and give up by the third bar.

And then there’s post-rock. No vocals. No choruses. Just slow-building instrumentals that go from whisper to roar. Explosions in the Sky and Godspeed You! Black Emperor turned rock into film scores for imaginary movies. It’s not about hooks. It’s about emotion through texture.

How Subgenres Are Born

Subgenres don’t appear out of thin air. They’re usually born from three things:

- Technology - When affordable drum machines hit the market in the 80s, house and techno exploded. When FL Studio became popular in the 2000s, bedroom producers started making hyperpop and bass music.

- Cultural shifts - Grunge didn’t emerge because someone wanted to be “angry.” It came from Seattle’s economic decline, isolation, and the feeling that mainstream rock had lost its soul.

- Hybridization - When metal meets hip hop, you get rap metal. When reggae meets dub, you get dancehall. When jazz meets electronic, you get nu-jazz. The most exciting subgenres happen at the edges, where genres collide.

Look at hyperpop. It’s a mashup of pop melodies, EDM distortion, punk energy, and internet humor. Artists like 100 gecs and Charli XCX use Auto-Tune like a weapon. Their songs are loud, glitchy, and intentionally overwhelming. It’s not for everyone. But it’s the sound of Gen Z saying: "I don’t care if it breaks the rules - I made this to feel something."

Why You Should Care

Knowing subgenres isn’t about being a music nerd. It’s about hearing music more deeply. When you know the difference between lo-fi and chillhop, you don’t just pick a playlist - you pick a mood. When you understand the difference between old-school boom-bap and modern trap, you hear the evolution of a culture.

Artists use subgenres to signal belonging. If you’re into dark ambient techno, you’re not just listening to music. You’re part of a community that values silence, space, and slow tension. If you love screamo, you’re connecting with a scene that turned emotional pain into sonic catharsis.

And if you’re a creator? Knowing subgenres gives you tools. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel. You can take a subgenre’s structure - say, the triplet hi-hats of drill - and mix it with a folk melody. That’s how new sounds are made.

Where to Find Them

Spotify playlists are full of generic labels. But if you dig deeper, you’ll find the real stuff. Try searching for "UK drill playlist 2025" or "post-rock ambient mix" or "acid house 1992". Look at Bandcamp - it’s still the best place to find underground subgenres. Labels like Hyperdub, Planet Mu, and Deathbomb Arc specialize in niche sounds.

YouTube channels like "The Sound of Music" and "Subgenre Explained" break down obscure styles with audio examples. Reddit communities like r/WeAreTheMusicMakers and r/IDM are full of people who know exactly what makes a track "future garage" versus "chillstep."

Don’t just listen. Compare. Put two tracks side by side - one from 1995 and one from 2024 - and ask: What changed? The tempo? The drums? The way the vocals are treated? That’s how you learn.

Subgenres Are Alive

There’s no official list. No committee decides what’s a subgenre. It’s organic. Right now, in Melbourne, in Berlin, in Lagos, in Seoul, someone is blending traditional drums with synthwave. Someone is sampling a Buddhist chant over a footwork beat. Someone is turning a TikTok sound into a full album.

Subgenres are how music stays alive. They’re the cracks where innovation slips through. The next big thing won’t be called "pop" or "rock." It’ll be something no one’s heard before - and someone, somewhere, will already be calling it by name.

What’s the difference between a music genre and a subgenre?

A genre is a broad category - like rock, hip hop, or electronic. A subgenre is a more specific style within that genre, defined by unique traits like tempo, instrumentation, or cultural roots. For example, "hip hop" is the genre; "boom-bap" and "trap" are subgenres. Subgenres help listeners and creators pinpoint exact sounds and moods.

How do new music subgenres get named?

There’s no official naming body. Names usually come from fans, bloggers, or DJs first. Sometimes they’re sarcastic - like "chillwave," which started as a joke. Other times, they’re descriptive - "math rock" refers to complex rhythms. Once a term sticks in online communities, it spreads. If enough people use it, it becomes real.

Can a subgenre disappear?

Yes, but rarely completely. Subgenres fade when they lose cultural relevance or get absorbed into newer styles. For example, "crunk" was huge in the early 2000s but faded as trap took over. But elements of crunk - like shouted hooks and heavy 808s - live on in modern trap. So it doesn’t vanish; it evolves.

Why do some subgenres sound so similar?

Because they often share the same tools. A producer using FL Studio and a sample pack might make something that sounds like both future bass and chillhop. The difference comes down to small details: the type of reverb, the drum pattern, the vocal processing. To the casual listener, they sound alike. To someone who’s studied them, the gaps are obvious.

Is it possible to create a new subgenre today?

Absolutely. All it takes is a unique combination of influences, a distinct sound, and a community that adopts it. Look at hyperpop - it didn’t exist five years ago. Now it has its own festivals. The tools are easier than ever. You don’t need a studio. Just a laptop, curiosity, and the courage to break the rules.