Music doesn’t stay still. It never has. But in the last 20 years, the pace of change has exploded. What used to take decades to evolve - like blues turning into rock - now happens in months. A producer in Tokyo drops a track with distorted 808s and field recordings from a rainy alleyway, and suddenly, a new subgenre is trending on TikTok. By the time you hear it in a club in Berlin, it’s already being called something else. This isn’t just innovation. It’s subgenre revolution.

What Even Is a Subgenre?

A subgenre isn’t just a fancy label. It’s the result of real people doing something new with existing tools. Take hip hop. In the 1970s, it was about beats, rhymes, and block parties. By the 2010s, you had trap - a sound built on skittering hi-hats, deep 808s, and lyrics about street life. Trap wasn’t just ‘hip hop with more bass.’ It was a cultural shift. It came from Atlanta, not New York. It used different software. It spoke to a different generation. That’s a subgenre: a distinct sonic identity born from a specific scene, technology, or attitude.

Same with electronic music. In the 1990s, techno was mostly about machines and repetition. Today, you’ve got acid house, future bass, drill ‘n’ bass, and vaporwave - each with its own rules, mood, and fanbase. Future bass uses pitched-up vocal chops and wobbly synths. Vaporwave loops 80s elevator music and slows it down until it feels like a dream. These aren’t just variations. They’re new languages.

Why Now? The Tech That Changed Everything

Before the internet, subgenres formed slowly. You needed a local scene - a club, a radio station, a record shop. If you lived in rural Ohio in 1985, you probably never heard grindcore. Now? A 16-year-old in Lagos can download FL Studio for free, watch a YouTube tutorial on how to make hyperpop, and upload a track to SoundCloud by midnight.

Software made it possible. Plugins like Serum, Omnisphere, and Kontakt turned laptops into full studios. AI tools now help producers generate drum patterns or even melodies in seconds. Distribution is instant. Discovery is algorithm-driven. You don’t need a label. You just need a unique sound and a hashtag.

Platforms like TikTok act like sonic accelerators. A 15-second clip of a track with a glitchy vocal chop can go viral. That sound gets copied, remixed, and layered with new elements. Within weeks, it’s a subgenre. Look at ‘cloud rap’ - a hazy, melancholic style that blew up after artists like Lil Uzi Vert and Playboi Carti used it. It didn’t come from a music school. It came from bedroom producers and viral memes.

Subgenres Are Cultural Mirrors

Every subgenre tells a story. Not just about music - about identity, politics, and emotion.

Grime emerged in early 2000s London. It was fast, aggressive, and raw. It used UK garage rhythms but added rapid-fire MCing in Cockney accents. It wasn’t just music. It was a voice for working-class youth in a city that ignored them. The same way drill music from Chicago became a grim snapshot of street violence, and then Brooklyn drill turned into something colder, more calculated.

Then there’s lo-fi hip hop. It’s slow, dusty, and comforting. It doesn’t shout. It whispers. It’s the soundtrack for students pulling all-nighters, remote workers in Tokyo, and anxious millennials in Melbourne. It didn’t come from a label. It came from YouTube channels playing rain sounds over slowed-down jazz samples. People didn’t just listen - they used it to cope.

Subgenres don’t just reflect culture. They create communities. Reddit threads, Discord servers, and Instagram hashtags become gathering places. Fans don’t just like the sound - they identify with it. They wear the aesthetic. They quote the lyrics. They treat it like a religion.

How Subgenres Die (And Sometimes Come Back)

Not all subgenres last. Many die because they get overused. Look at dubstep. In 2010, it was everywhere - heavy wobbles, drops that shook stadiums. By 2015, it was everywhere. Too much. People got tired. The sound became predictable. It lost its edge.

But death isn’t always the end. Dubstep didn’t vanish. It split. Some producers moved into bass house. Others went full experimental, blending it with ambient or industrial. A few even brought back the old wobbles - but now, it’s ironic. Nostalgic. A throwback. That’s how music cycles. What’s outdated today becomes vintage tomorrow.

Same with vaporwave. It was a joke at first - a parody of 90s consumerism. Then people started making real music with it. Artists like Macintosh Plus and Saint Pepsi turned it into something hauntingly beautiful. Now, it’s a full-blown aesthetic movement with its own fashion, art, and philosophy.

The Rise of Micro-Subgenres

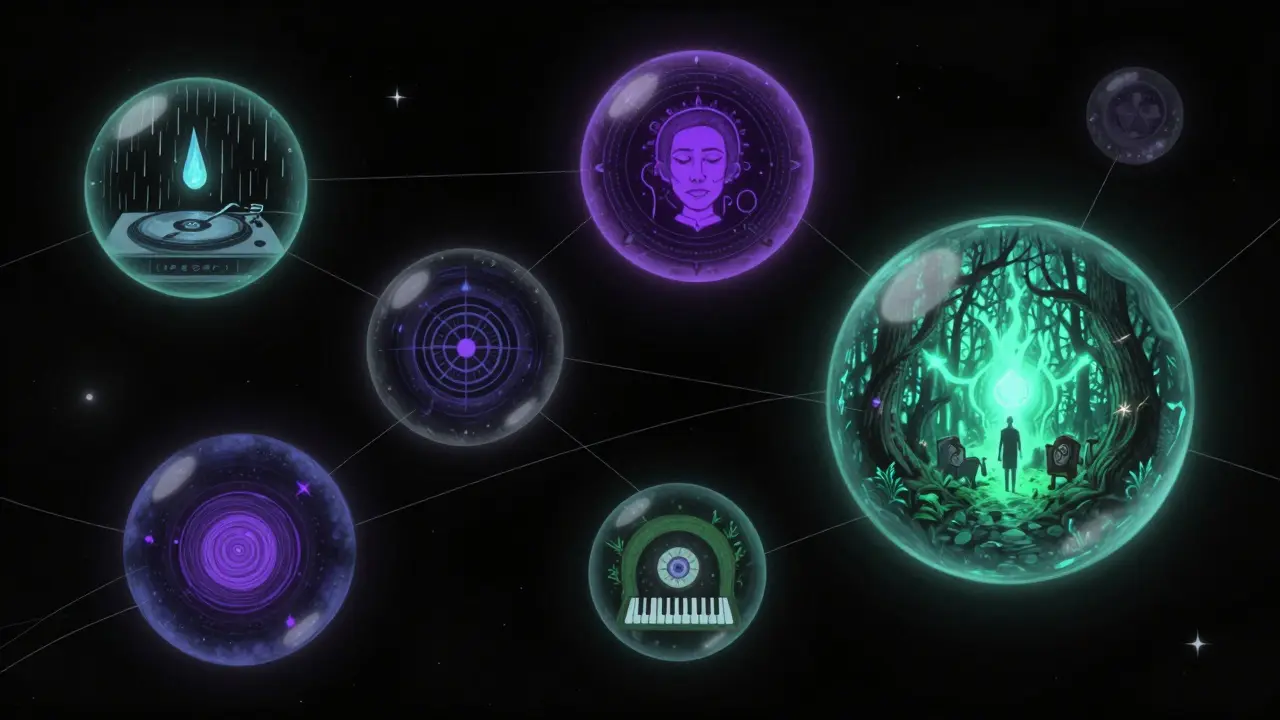

Today, the lines are blurring so fast that we’re seeing micro-subgenres - genres within genres.

Take ‘witch house’ - a dark, occult-themed style that mixes slowed-down hip hop beats with haunting synths and eerie vocal samples. Or ‘bedroom pop’ - lo-fi, emotionally raw songs made on iPhones, often by teenagers. Then there’s ‘chillwave,’ ‘seapunk,’ ‘noise pop,’ and ‘goblin core’ - yes, that’s a real thing. It’s dreamy, fantasy-inspired electronic music with soft vocals and medieval synth melodies.

These aren’t just marketing terms. They’re labels people use to find their tribe. If you’re into ‘goblin core,’ you’re not just listening to music. You’re joining a world. You’re wearing oversized sweaters, listening to songs about forests and ghosts, and sharing playlists with strangers who feel the same way.

Platforms like Spotify now have playlists for these micro-genres. ‘Cottagecore Mix,’ ‘Dark Academia Beats,’ ‘E-girl Trap’ - they’re not just algorithm suggestions. They’re cultural buckets. People curate their identities around them.

What This Means for Artists and Listeners

For creators, this is both freedom and pressure. Freedom because you don’t need permission to start something new. Pressure because the shelf life of a sound is shorter than ever. A subgenre can explode and fade in six months. You have to move fast. You have to be authentic. You can’t fake it - audiences smell inauthenticity instantly.

For listeners, it’s overwhelming. There are now over 1,200 recognized subgenres of electronic music alone. How do you find what you love? The answer isn’t just scrolling. It’s curiosity. Ask yourself: What mood am I chasing? Calm? Aggression? Nostalgia? Loneliness? Each subgenre carries an emotional signature. Find the one that matches your inner state.

Try this: next time you hear a track that sticks with you, don’t just save it. Ask: What makes this different? Is it the rhythm? The texture? The silence between beats? That’s how you start understanding subgenres - not by memorizing names, but by listening deeply.

The Future: No More Boundaries

The next wave won’t be about adding new labels. It’ll be about breaking them.

Artists are already blending subgenres like paint. A track might start as hyperpop, shift into k-pop, then dissolve into ambient noise. Algorithms can’t always categorize it. Labels don’t know where to file it. And that’s the point.

Gen Z and Alpha listeners don’t care about genres. They care about feeling. If a song makes them feel seen, it doesn’t matter if it’s called ‘trap metal’ or ‘emo folktronica.’

What’s next? Maybe subgenres will disappear entirely. Maybe we’ll just have ‘moods’ instead of genres. Maybe AI will generate music tailored to your heartbeat and mood in real time. But one thing’s certain: music will keep evolving. Not because someone in a boardroom decided to. But because someone in a bedroom, somewhere in the world, pressed play - and made something no one had heard before.

What’s the difference between a music genre and a subgenre?

A genre is a broad category like rock, hip hop, or electronic. A subgenre is a specific style that branches off from it. For example, punk rock is a subgenre of rock. Trap is a subgenre of hip hop. Subgenres have distinct sounds, rhythms, production techniques, and cultural roots that set them apart from the main genre.

How do new subgenres get named?

There’s no official naming body. Names usually come from fans, critics, or artists themselves. Sometimes it’s a joke - like ‘witch house’ or ‘goblin core.’ Other times, it’s a geographic reference - like ‘Chicago drill’ or ‘London grime.’ Once a term sticks on social media or in music blogs, it spreads. If enough people use it, it becomes official.

Can you make a career out of a niche subgenre?

Absolutely. Many artists thrive in micro-genres because they attract loyal, passionate fans. You don’t need millions of listeners - just a few thousand who deeply connect with your sound. Artists like Yaeji (experimental pop/techno) and Arca (avant-garde electronic) built global followings by staying true to unique, niche styles. The key is consistency and authenticity - not chasing trends.

Why do some subgenres feel like trends and others feel permanent?

Trendy subgenres often rely on a single sonic trick - like a specific synth or vocal effect - and get overused quickly. Lasting subgenres have deeper roots: a cultural movement, emotional resonance, or innovation in production. Trap didn’t fade because it changed how hip hop was made, not just how it sounded. Lo-fi hip hop endures because it fills a real emotional need - calm in a chaotic world.

Is it harder to stand out now with so many subgenres?

It’s harder to be heard, but easier to be found. With so many subgenres, you’re not competing with everyone - just the people who like what you like. If you make ‘dark ambient folk’ music, you’re not fighting Taylor Swift. You’re competing with three other artists in that tiny space. Find your niche, serve it well, and your audience will find you.

Subgenres are the heartbeat of modern music. They’re where creativity breaks free from tradition. Where the quietest bedroom producer can change the sound of the world. You don’t need a studio. You don’t need a label. You just need a idea - and the courage to press record.