Reggae music wasn’t born to be background noise. It didn’t rise from studio sessions or radio trends. It came from the backstreets of Kingston, the hills of Trench Town, and the quiet prayers of people who had been told their voices didn’t matter. Every drumbeat, every bassline, every offbeat guitar chop was a protest. Every lyric was a reminder: you are not invisible.

The Sound of Resistance

Before reggae became global, it was local. It was the sound of men and women waking up to the same injustice they’d faced for generations. In the 1960s, Jamaica was still feeling the weight of colonial rule, economic neglect, and systemic silence. The music that came out of that time didn’t whisper. It shouted. And it did it with rhythm.

Reggae evolved from ska and rocksteady, but it slowed down. It made space. That space wasn’t empty-it was filled with meaning. The bass didn’t just keep time; it pulsed like a heartbeat. The snare hit on the second and fourth beats-the one drop-felt like a foot stomping on the ground to say, I’m still here. The guitar, choppy and sharp, cut through like a voice refusing to be drowned out.

It wasn’t about speed. It was about presence. And that presence carried truth.

Bob Marley and the Voice of the Voiceless

If you know one name in reggae, it’s Bob Marley. But he wasn’t just a singer. He was a vessel. His songs didn’t come from fantasy-they came from lived experience. Get Up, Stand Up wasn’t a slogan on a T-shirt. It was a call to action written after watching a friend get beaten for speaking out. Redemption Song didn’t just borrow from Marcus Garvey-it carried his spirit forward, stripped of poetry, raw with urgency: Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery.

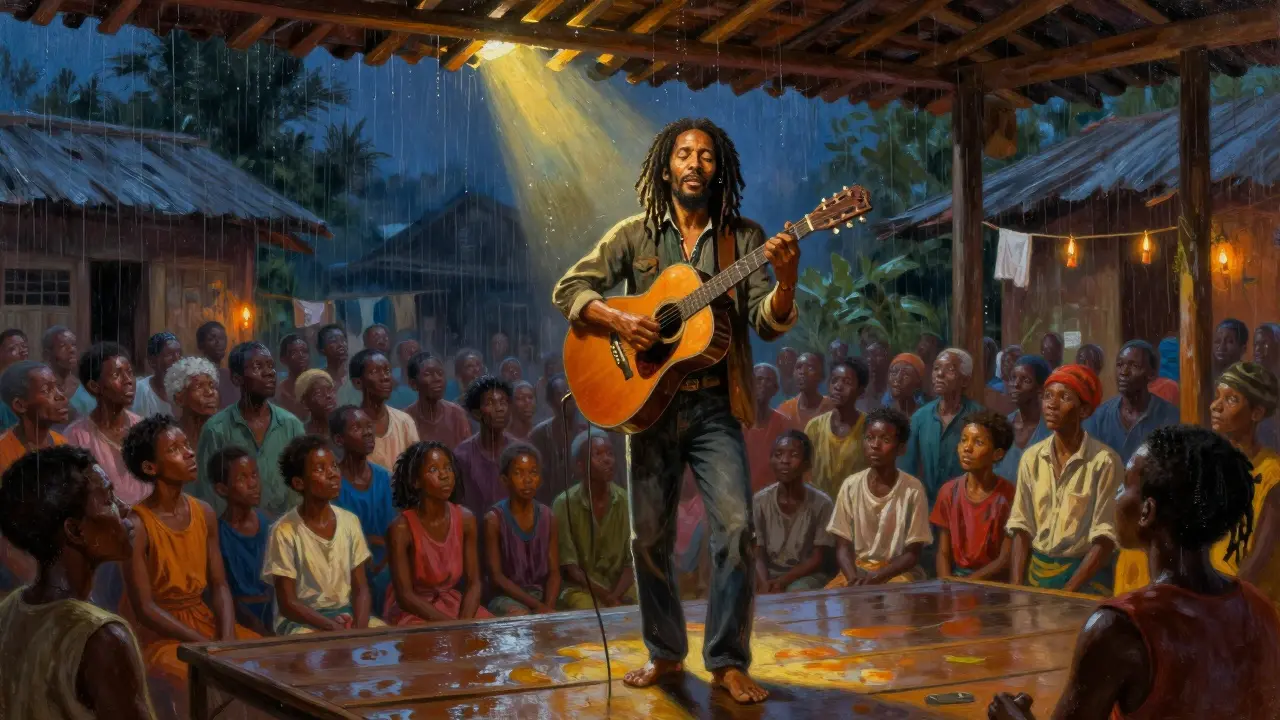

Marley didn’t write songs for stadiums. He wrote them for the people who couldn’t afford to go to them. He played in village squares, in open-air markets, in churches where the roof leaked but the message didn’t. His music traveled not because it was polished, but because it was honest. When he sang War, quoting Haile Selassie’s 1963 UN speech, he didn’t soften the words. He made them louder.

That’s why, even now, when someone in a protest march in Brazil, South Africa, or Melbourne sings One Love, they’re not just singing a hit. They’re claiming a lineage.

Rastafarianism: More Than a Style

You can’t talk about reggae without talking about Rastafarianism. But it’s not just about dreadlocks, ganja, or the colors red, gold, and green. Rastafarianism is a spiritual movement born from oppression. It emerged in Jamaica in the 1930s, rooted in the belief that Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia was the messiah-a Black king who defied colonial narratives. For Black Jamaicans, Selassie wasn’t just a leader. He was proof that liberation was possible.

Reggae became the soundtrack to that belief. Songs like Babylon System didn’t just criticize the government-they named the system: colonialism, capitalism, racism. The Babylon in reggae isn’t a place. It’s a structure. It’s the police, the courts, the schools that taught you to be ashamed of your skin. And reggae? It was the resistance manual set to music.

Even today, when you hear a reggae artist chant Jah Rastafari, they’re not just saying a phrase. They’re declaring identity. And that identity is political.

How Reggae Changed the World

Reggae didn’t stay in Jamaica. It traveled. In the UK, it gave voice to Black youth facing police brutality and housing discrimination. In the US, it influenced hip-hop’s early beats and political lyrics. In Africa, it became a symbol of Pan-African unity. In Australia, it found a home among Indigenous communities who saw their own struggles mirrored in the lyrics.

In 1978, Marley performed a free concert in Kingston called One Love Peace Concert. Two rival political leaders-Michael Manley and Edward Seaga-stood on stage together, shaking hands. The crowd roared. That moment didn’t end the violence. But it proved music could interrupt hate, even for a few hours.

Today, UNESCO recognizes reggae as an Intangible Cultural Heritage. Not because it’s pretty. But because it’s powerful. It’s the only music genre officially honored by the UN for its role in promoting social justice.

The Instruments of Rebellion

Reggae’s sound is simple, but it’s not easy to replicate. The bass is deep, heavy, and melodic-often played with fingers, not a pick, to give it a warm, human pulse. The drums are minimal: kick on beat three, snare on beat two and four. The rhythm guitar chops on the offbeat, like a heartbeat skipping just enough to keep you alert.

The organ and piano add texture, swirling like incense in a prayer circle. And then there’s the voice-not always perfect, but always real. You hear the rasp, the breath, the pause before a line. That’s not a flaw. That’s the point.

Many reggae artists played their own instruments. They didn’t wait for studios or producers. They built their own sound systems, loaded them onto trucks, and played in neighborhoods no one else cared about. That’s how the music spread. Not through labels. Through community.

Reggae Today: Still Fighting

Reggae isn’t a relic. It’s alive. In Kingston, young artists like Kabaka Pyramid and Protoje blend reggae with hip-hop and electronic elements, but they still sing about police violence, land rights, and mental liberation. In New Zealand, Māori musicians use reggae to reclaim language and land. In France, artists from immigrant communities use it to challenge xenophobia.

Even in Australia, Indigenous musicians like Dan Sultan and The Pigram Brothers have used reggae rhythms to tell stories of dispossession and resilience. One song, My Country, opens with a didgeridoo and ends with a chant in Noongar language. It’s reggae, but it’s also deeply Australian.

When you hear reggae now, it’s not nostalgia. It’s a continuation. The same questions are still being asked: Who gets to speak? Who gets heard? Who gets to be free?

Why It Still Matters

Reggae music doesn’t ask you to dance. It asks you to think. It doesn’t ask you to buy a ticket. It asks you to stand up.

In a world where algorithms decide what we hear, where music is packaged as entertainment, reggae remains a radical act. It reminds us that sound can be a weapon. That rhythm can be resistance. That a simple three-chord song, played on a worn-out guitar in a dusty yard, can echo louder than any news headline.

It’s not about the genre. It’s about the message. And that message hasn’t changed: freedom isn’t given. It’s sung.

What makes reggae music different from other genres?

Reggae stands out because of its rhythm-specifically the one-drop drum pattern and the offbeat guitar chops. But more than its sound, it’s defined by its message. Unlike pop or rock, which often focus on romance or partying, reggae centers on social justice, spiritual resistance, and liberation. Its roots are in the struggles of Black Jamaicans, and its lyrics carry the weight of real-world oppression.

Is reggae music still relevant today?

Absolutely. Reggae is alive in protest movements worldwide. From Indigenous communities in Australia to youth in Brazil fighting police violence, reggae rhythms and lyrics are used to express resistance. Modern artists blend it with hip-hop, electronic, and Afrobeat, but the core message-freedom, truth, and dignity-remains unchanged. UNESCO even recognizes it as an Intangible Cultural Heritage for its ongoing social impact.

Why is Bob Marley so central to reggae?

Bob Marley didn’t just popularize reggae-he gave it a global voice. His songs turned local Jamaican struggles into universal messages of peace and resistance. He took Rastafarian beliefs and made them audible to millions. But more than that, he refused to let the music be commercialized without its soul. He played for the people, not just the crowd. His legacy isn’t just his hits-it’s the fact that his songs are still sung in protests 40 years later.

How did Rastafarianism influence reggae music?

Rastafarianism gave reggae its spiritual and political foundation. The movement, born in Jamaica in the 1930s, revered Emperor Haile Selassie I as a symbol of Black divinity and liberation. Reggae artists used music to spread Rastafarian teachings: rejection of Babylon (oppressive systems), love for Africa, and the sacredness of nature. Lyrics about Zion, Jah, and redemption aren’t religious metaphors-they’re political statements. Without Rastafarianism, reggae would be just another genre. With it, it became a movement.

Can anyone play reggae music, or is it only for Jamaicans?

Anyone can play the notes, but playing reggae with truth requires understanding its history. Non-Jamaican artists who respect its roots-studying its political context, honoring its spiritual depth, and listening to its original voices-can create powerful reggae. But when it’s stripped of its meaning and turned into a fashion or party trend, it loses its power. Reggae isn’t a style. It’s a stance. And that stance is earned through empathy, not imitation.